Sitting on the balcony of the lone hotel in Bsharre, I cracked open the leather-bound book. I looked at the Arabic words on the pages of The Prophet, Khalil Gibran’s literary masterpiece, which I just happened to be reading in his own hometown in Lebanon. Everything had come full circle. My years spent studying Arabic language and literature had guided me toward a career focused on the language of my forefathers. I sat back and dug into the book, knowing that everything made sense.

My journey to speak Arabic has been a combination of both my family origin and passion for international politics. My grandmother, Renee Maloof, was born to Joseph and Afdokia Maloof in 1926 in Washington Heights in New York City. Joseph and Afdokia hailed from a small mountain village of only 200 people, 50 miles east of Beirut, in Lebanon. They both spoke Arabic and for all of her childhood, my grandmother Renee was surrounded by everything Lebanese. She didn’t learn much Arabic herself, but her siblings, especially Waleed and Alice, became quite proficient in Lebanese Arabic. Later, Renee married an Irish man named Charles McCormick and they gave birth to my mother, also Renee, in 1950. After only a few years into my mother’s childhood, her own mother contracted tuberculosis and was not able to care for my mother or her siblings for years. My mother moved in with her grandparents, Joseph and Afdokia, and spent much of her childhood also surrounded by Lebanese culture and Arabic language.

My grandmother, Renee Maloof McCormick, spent her whole life working as an artist.

Fast forward to my birth and childhood. I was lucky enough to meet many of these relatives, first-generation children of Lebanese immigrants. I grew up eating hummus and baba ghanouj, dishes that I continue to cook for guests until this day. As I got older, I started to become fascinated by world politics. Once I got to college, I naturally chose to study Arabic. I was fascinated by the language and really appreciated the calligraphic writing style. At times, it was quite challenging, but I persisted.

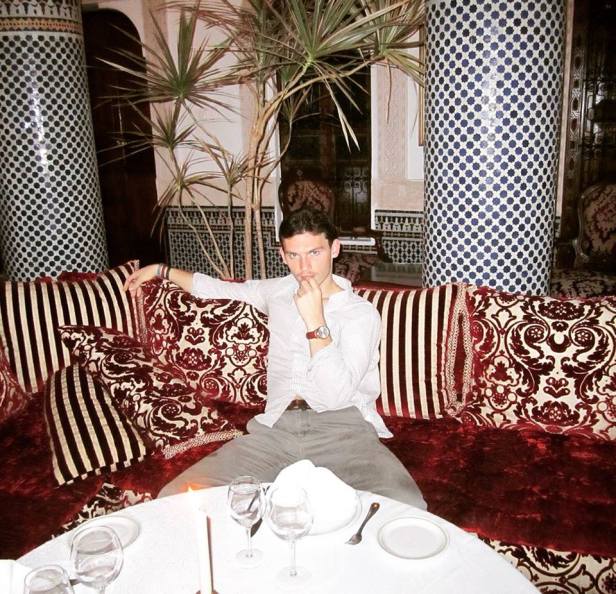

I then chose to study for a semester in Morocco. I had no idea how different the Moroccan dialect would be. I studied standard Arabic in my classroom in Morocco, only to walk out into the street and be forced to speak Moroccan Arabic. I was only there for four months, so I couldn’t learn much more than the basics of Moroccan Arabic.

Fes, Morocco, November 2012.

Still, I returned to the US with a newfound confidence in my Arabic. I remember, in January 2013, I made a point of striking up conversations with all of the Egyptians that I met at halal food carts in New York City. Starting back up at Connecticut College, I began to realize that my knowledge of Arabic could open up many doors for me. For the summer 2013, I landed a really excellent internship researching the Syrian civil war at the Institute for the Study of War, a think-tank in Washington D.C. The research director of the organization told me that my application stood out among many others because of my Arabic language skills.

As the new academic year began, I declared my self-designed major in Arabic Language & Literature to go along with my International Relations major. In addition to my Arabic coursework throughout my four years, I also researched Moroccan literature and wrote a paper analyzing sexual and political dissent in Mahmoud Saeed’s Ben Barka Lane. The research project allowed me the chance to combine my knowledge of Moroccan Arabic from my time spent abroad with my Arabic literature research skills gained from my time studying at Conn.

Having the major of Arabic has really made me stand out in the professional world. Similar to the reason for my hiring at the Institute for the Study of War, one of the main reasons I got my first job out of college as the coordinator of the American Corner cultural center in Tunis is because of my ability to speak Arabic. Once I found out I was heading to Tunisia, I focused one of my final papers on the theme of mental health in Hassan Nasr’s Dar al-Basha, a famous Tunisian work of literature. Even before going to Tunisia, I knew different themes of the culture from my literary research.

Wearing a traditional Tunisian djebba for Eid al-Fitr, July 2015.

In this context, I spent my first year at the American Corner, in a really dynamic and engaging job, which brought me into contact with young Tunisians every day. In the beginning, my knowledge of standard Arabic did not translate into fluency in talking with Tunisians. However, my knowledge of standard Arabic has been profoundly helpful in learning the Tunisian dialect, hence why I always recommend Conn students study Arabic first in the classroom.

In addition to my job at the American Corner, I also worked for a year as Student Affairs Coordinator at the Mediterranean School of Business. On top of that, I spent much of my time working as a freelance journalist, writing about Tunisian politics, culture, sports, and society.

Now, I speak mostly Tunisian Arabic, combined with some standard Arabic, and a bit of Lebanese Arabic. After two years in Tunisia, I can hold in-depth conversations with people, can conduct journalistic interviews in Arabic, and was even interviewed for 25 minutes on a national Tunisian radio station. I’ve also traveled to both Jordan and Lebanon and was able to communicate easily with locals there.

Me and my mother Renee in our family’s hometown of Zabbougha, Lebanon, August 2015.

Learning a language like Arabic, which is so different from English, has been a truly rewarding experience. It has been so enjoyable and you can tell how excited Arabic speakers become when a foreigner speaks to them in their mother tongue. My ability to speak Arabic has also contributed greatly to my future educational aspirations, since foreign policy professionals recognize that it is one of the most important languages to know in our modern age.

In September of this year, I am set to begin a dual-degree master’s program at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and School of Journalism. At the end of two years, I will have two master’s degrees: one in international affairs, the other in journalism. After that, I plan on either continuing to write about politics, society, and culture of countries in the Middle East and North Africa from Washington D.C. or New York City, or moving back to the region to work as a correspondent for a newspaper or website. I am not sure of the exact timing of my future career moves, but I am absolutely positive that I will spend a significant portion of my life living in Arabic-speaking countries like Lebanon, Tunisia, or Morocco.

If I could give one piece of advice to any first year students at Connecticut College with an interest in Arabic, Arab culture, politics, or religious studies, I would say go for it. Study Arabic and fully invest yourself in it. You won’t regret it. It is a difficult language, but anytime during my years studying Arabic at Conn, I could go to a professor, a native speaker, or an older student for extra help and they would actually invest a great deal of their times in me. That is unique. Professor Waed Athamneh grew this program from the ground up and I was lucky enough to be a part of its genesis.

The Arabic program at Conn also gives you the opportunity to study abroad, which lays the ground for future endeavours abroad. One of the best things you can do after graduating from college is moving abroad, as it helps you see a whole new perspective about the world. With a combination of speaking Arabic and experience living abroad, many doors will open up for you, just as they did for me. For all of the students currently studying Arabic at Conn, I want to tell you to stick with it. It is tough at times, but it is all worth it when you can go to a friend’s household and have full conversations in Arabic, making jokes in a language which isn’t your mother tongue.

On a more serious note, Arabic is the most important language to invest in. US foreign policy is fixated on the Middle East and North Africa and it is Conn’s duty to help contribute a new wave of future diplomats and peacemakers to help solve the crises that are tearing countries apart. Support for the Arabic studies program has never been more important and supporting Professor Athamneh’s hard work will pay major dividends going forward.

I can honestly say that I am beyond satisfied with the way my education and professional career have gone so far. Arabic has been the focal point of all of it.

Hi dear friend, I’ve just nominated you for the 3 quotes a day challenge, hope you enjoy, blessings.

This’s very different from what you normally post, hope you won’t mind!

LikeLike

شكرا كونور

LikeLike

This is such a great post! As a native Arabic speaker myself, I’ve never thought that there were that much opportunites of knowing the language in the US!

LikeLike

❤ I love this post Conor. I had no idea about your mom's background! How awesome!

LikeLike

Hello. My name is Andrea. My father and your grandmother, Renee were cousins. I grew up in Teaneck NJ, the town next to New Milford and spent much time with your grandparents and I knew your mom — she is older than I am. I don’t know why, but I woke up this morning thinking of my cousin Renee. So I googled her and came up with various links. I thought I would reach out and introduce myself and pass along my fond regards and memories.

LikeLike